Around the late eighth century BCE, someone composed The Odyssey.

Was it the blind bard we call Homer?

Perhaps.

Could it have been a series of poets who contributed to a growing oral tradition over centuries?

Possibly.

One thing is certain: the lengthy epic poem we now attribute to Homer is one of the foundational pillars of Western literature. Today, the story of Odysseus’s long journey home continues to challenge readers to reflect on “Big Questions” about what it means to be human, and to think about what it means to feel adrift in a rapidly-shifting world, when everything is changing.

The world of The Odyssey reflects the aftermath of the Trojan War. The poem grapples with loss, displacement, and the long work of rebuilding lives and communities. While the Iliad tells the story of the war itself, The Odyssey asks a different question: How does a once-great hero return home after many years of exile, and who must he become in order to reclaim his rightful place?

The epic follows the journey of Odysseus, a king whose return to Ithaca has been delayed for ten years after the fall of Troy. It is also the story of those who wait for him: his wife Penelope, and his son, Telemachus. Set in a rich virtual world filled with gods and monsters, The Odyssey invites us to consider enduring human concerns. Readers learn about the forging of character, the nature of desire, the responsibilities of leadership, and the consequences of choice.

Across twenty-four books, Homer presents both an epic adventure story and a moral vision that challenges us to think about what it means to live wisely in a fragile and uncertain world. Today, we live in a moment marked by cultural fragmentation and restless distraction. Our public life is loud, reactive, and often unmoored from memory. We have unprecedented access to information, but perhaps less clarity than ever about how to flourish as human beings. What a book like The Odyssey asks of us is something counter-cultural: slow reading, fueled by sustained attention. That’s where the magic happens.

Odysseus does not return to Ithaca as the same man who left for Troy. He must learn restraint after pride, patience after glory, listening after command. Telemachus has grown up in a house overrun by men who consume without building. Penelope holds a fragile kingdom together through quiet endurance. These are not ancient problems. They are our problems, too. Page by page, Homer’s epic rewards its readers’ patience and reminds us that character is formed slowly, often invisibly, through a series of choices that may seem small but ultimately determine the fate of individuals and kingdoms.

How does a leader exercise strength without arrogance?

How does a young person grow into courage without becoming cruel?

How does a household, or a nation, survive when its institutions are under strain?

What habits, what loyalties, what disciplines actually hold a community together when no one seems to be watching?

To read The Odyssey now is to resist the assumption that we are the first generation to face upheaval. It is to step into a long conversation about desire, fidelity, leadership, and homecoming.

I recommend the English translation of the Odyssey by Robert Fagles. (Bob, who was a mentor to whom I much indebted, also translated the Illiad. His version preserves the music and moral gravity of the poem while making it accessible to modern readers.)

Disclaimer: As an Amazon Associate, we earn from qualifying purchases. Amazon and the Amazon logo are trademarks of Amazon.com, Inc. or its affiliates.

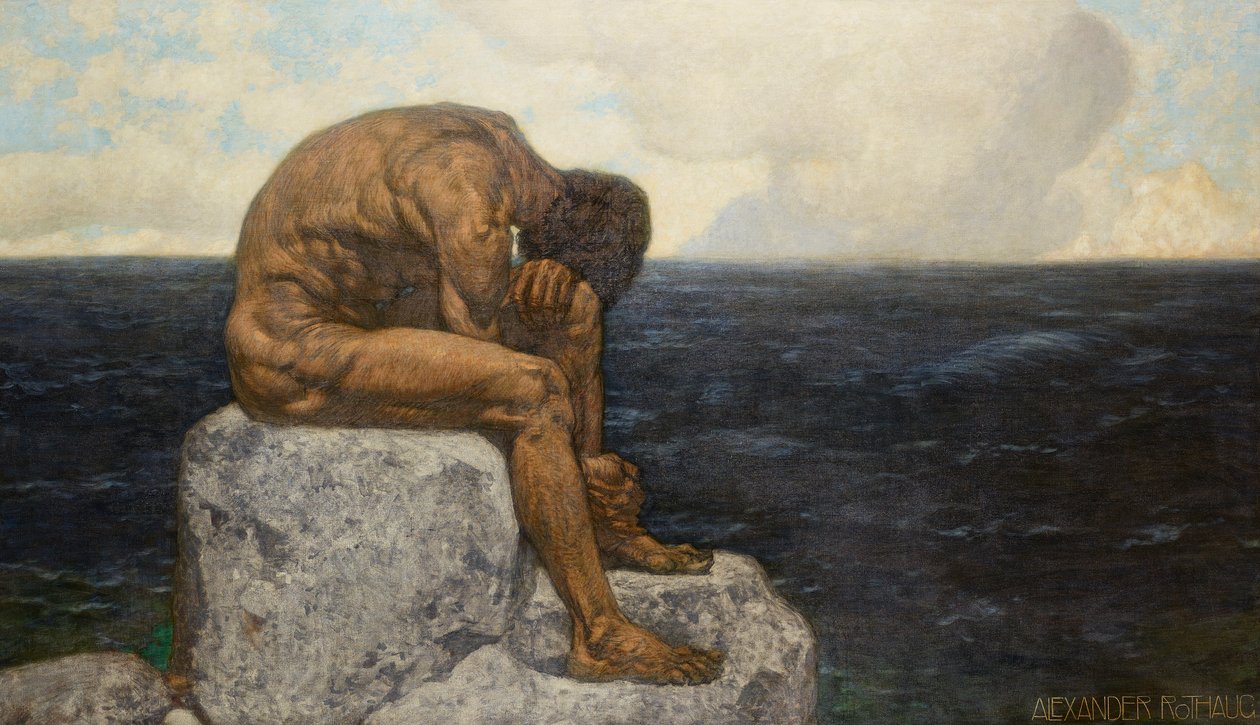

Odysseus (Longing for Home) by Alexander Rothaug